Image by Johnnyhurst

In 1911, my great-grandmother’s sister and her family left their diaspora home in the Ukraine, then a province of the Russian Empire and sailed to the New World. Where they actually landed and what exactly happened to them, I do not know. Perhaps they meant to make their way to America, but we know they ended up in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The next time our branch of the family, the dumb branch, had heard of my North American relatives was when they found us, in the Soviet Union, during the détente period of the Cold War in the late 1960’s. One of the “asks” from the American side in the détente negotiations was the opening of a channel for separated Jewish families just like ours to try and find each other. And so when I was six or seven years old, my grandmother received a letter written in Yiddish from her niece Sarah, currently of Montreal, who she never suspected had even existed. Both families were sure the other one had long since perished, but only the Canadian side had a good reason for it. Beneficiaries of at least partially factual Western news coverage, they knew of the devastation the Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent Civil War had wrought. They knew of the deadly Stalinist repressions of the 1930’s and of course, they knew of the Holocaust.

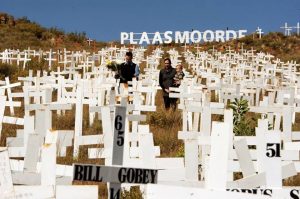

The Hi-Tech Traditionalist: A Place The Tribe Can Truly Feel At Home, Lost In South Africa

My family, in contrast, was the victim of the Soviet fake news propaganda. While we tried hard not to give it credence, it was impossible to completely ignore the constant barrage of “news” emanating from our obligatory government installed wall-plugged “radio” painting life in the West as a hellish struggle for survival, where people dodged starvation only to be killed by violent criminals. Soon after the connection was established and more letters arrived carrying inside them little notes from Soviet censors clearing their contents, it started to dawn on us that our suspicions as to the inaccuracy of Soviet “news” were well-founded indeed. In fact, Soviet news were unimaginably more fake than we gave them credence for. Our relatives led a lifestyle that to us could only be described as magically alien. They owned their own town home and a cottage on a lake. They had disposable incomes. They owned a car. Compared to what (I now know) was a typical North American middle class existence, we were simply dirt poor. At that time we still lived in a communal apartment, sharing what must have been the 3,000 square foot or so town apartment of a pre-revolutionary merchant or professional, with five (!) other families. The kitchen and the bathroom were shared. The living and dining rooms were long since chopped up into small bedrooms, so the kitchen was the only place where the twenty or so inhabitants could “hang out”. Cooking, washing clothes, going to the bathroom, was all done in turns. My parents and I shared a bedroom that was at most the size of a Dodge Caravan. We had our lives, which is likely more than could be said for the previous owners of the apartment, but that was pretty much all we had.

Soon, our Canadian relatives started sending us money; Canadian dollars that, since holding foreign currency was illegal in the USSR, were converted into vouchers that could be redeemed for imported goods in special stores that catered to Communist Party nomenklatura, foreign diplomats, and folks like us, who were the lucky recipients of foreign aid. As a result, two things happened: I became the only kid in my school who owned a zipper and I became a lifelong hater of communism and all totalitarian ideologies. I also figured out that the other branch of my family, the one that almost sixty years prior had made the incredibly risky decision to leave a country that their ancestors first came to many centuries ago and travel to an unknown land across the ocean with few possessions and no money, was, would you have guessed it, the smart branch. We were the idiots.

I’ve written on these pages of the impending ethnic cleansing of the one and a half million Boers in South Africa. One of these folks, having read my piece, commented that I was placing the blame for their fate on the Boers themselves, something that would, of course, be entirely unjust. This comment raises a very interesting and topical question: is the proper assignment of blame important. The answer, I would like to posit, is twofold. There is no denying that blame in the sense of culpability must be placed, as soon as possible, on the perpetrators of the crime. These perpetrators need to be identified and to any possible extent, punished. No Jew was to blame for their death or suffering in the Holocaust, no matter what they chose to do or not to do. Germany was culpable as a sovereign nation along with individual Germans and others who participated in the torture and murder of Jews and other minorities and conquered peoples. Germany has paid reparations to the Jewish people as represented by the State of Israel. Individual Germans and others who helped them were held personally accountable and some merited and received the highest degree of punishment, though far too many have eluded justice.

The sole culpability for any action unlawfully taken against any South African citizen, especially if it targets South Africa’s indigenous Europeans, the Boers, lies with the individual criminals who undertake this action and the current South African regime that gives them cover and indeed encourages their behavior. Perhaps a time will come when both the individuals and the regime will be brought to justice for their deeds. But examined from a different perspective, the question of blame or culpability loses its importance. What does it matter WHY both my grandfathers were killed fighting the Nazis in the ranks of the Red Army? What matters is that they were killed, and that their wives were widowed before their mid-thirties, and that my mother and my father grew up without fathers. What matters is that they were killed because the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in a criminal act of international aggression AND because unlike many other Jewish families of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, their families CHOSE not to emigrate to North America or to Palestine.

Choosing to take that shortcut alone at night through a sketchy part of town is the necessary condition to your being held up at gunpoint. This in no way exculpates the criminal who CHOSE to complete the sufficient requirement for the crime and actually go through with the robbery. The criminal should face the full brunt of the law. You should have known better. By completing the necessary requirement towards your own robbery, you created the conditions that allowed the culpable party to act. There is no moral equivalency; your choice of taking the shortcut was not immoral, let alone criminal; it was simply dumb.

Source National Archives

Nothing that the Boers did in the past, neither their catastrophic choice of exclusion of other races from South Africa’s erstwhile magnificence, nor the odious fruit of that choice, the apartheid system, justifies in any degree the genocidal acts that they are now being subjected to. And yet, these choices were as dumb as they were irreversible. These choices created the necessary condition for the Boers to be facing the hard choice they are facing now: leave your ancestral lands or be killed on them.

Democrats Have Been Colluding With America’s Enemies For Decades, Trump Just Exposed Them

Perhaps, now that I think of it, it was those letters from our Canadian relatives that caused my father to become, as we would say today, woke. All I know is that if Pravda, the “Organ of the Communist Party of the USSR” had printed that the sun would rise in the east tomorrow, my dad would be looking to the west for sunrise. In the early seventies, a time that in 20-20 hindsight is now recalled as the beginning of the “stagnation” period in the USSR’s short history, a period that led to its eventual demise, my dad did not need the benefit of hindsight; he knew that despite the propaganda the USSR was not a world power. It was a house of cards built on nothing but lies. And so, in January of 1973, he took the nearly suicidal risk of asking the Soviet authorities to let us emigrate to Israel. Being refused, my parents knew full well, would have meant a life in limbo: the loss of both their jobs, my expulsion from elementary school, a life of begging for handouts from friends and relatives, a living hell. His own sister and her husband called him crazy, but my dad’s mind was made up.

Image by Johnnyhurst

One day soon after classes started in the fall of that same year, as soon as everyone had taken their seats first thing in the morning, I was called by the teacher to stand before my third grade class. I was naturally terrified, but more so puzzled; I was a good student and had done nothing wrong. On my way down the aisle from my desk to the chalkboard I recalled the KGB agents that were stationed outside our apartment widow from the first day we had applied for an exit visa and I knew: I was being expelled. As I stood there facing the thirty-odd of my fellow classmates, the teacher approached me and brusquely untied and removed my red Young Pioneers necktie. With it in hand, she faced the class. “Pletner, Baruch Isayevich,” she said, “is being expelled from the Young Pioneers organization and from this school, because his parents have chosen to leave our glorious homeland and emigrate to the capitalist and terrorist state of Israel.” She paused. “Get your things and go,” was all she said next, and that was what I did.

It was not my aunt’s “fault” that the USSR was as it was. It was not her fault that the Soviets inevitably lost the Cold War. It was not her fault that following that loss the country that I remember her calling the “greatest power on earth” went out in 1990 with nary a whimper, disintegrating into chaos and economic collapse. These things were not her fault, and yet, when she and her family appeared two years later with nothing but the clothes on their backs on the front porch of my parents’ country house with its flowering rose bushes and the new Japanese sedan in the driveway, there all of us were; a cautionary tale of irreversible decisions.