Last week, the propaganda machine of the Albanian government went into overdrive: A Harvard professor had written about the economic “miracle” which the country is going through. As we soon explained though, Ricardo Hausmann, the current director of the Center for International Development (CID) at the Harvard Kennedy School for Government, had not reached his conclusion due to some meticulous academic research. He had been handsomely paid for his services by the Open Society Foundation, which is closely linked to the Rama government. Writing a propaganda piece was simply the cherry on the top.

The Trans Adriatic Pipeline…From Controversy To Archeology

Unfortunately for his credentials and his boosters, he couldn’t have done a worse job. Many of his claims appear out of thin air, with no data or facts to back them up. Economic growth theory, which is Hausmann’s field, would refute many of the implications of these fabricated facts. That is unfortunate, because when he really tries, Hausmann can be a good economic narrator, even though his facts would not be as pleasing for the current Albanian government. In many ways, it seems like he was writing a bad piece in order to tell the world he was faking it.

Let’s have a look at some of his main claims and see how they can easily be debunked through simple graphs and data.

Hausmann’s first claim concerns the Albanian government’s financing abilities and is closely connected to the recent successful eurobond sell-off. He claims that:

[Five years ago] Access to external financial markets had collapsed and domestic interest rates were sky high….

[Now] At a time when emerging-market economies as diverse as Argentina, Turkey, Nigeria, and South Africa face plummeting currencies and rising interest rates, Albania has its lowest interest rates on record and a strengthening currency. It now has the lowest sovereign spread for any country in its rating class.

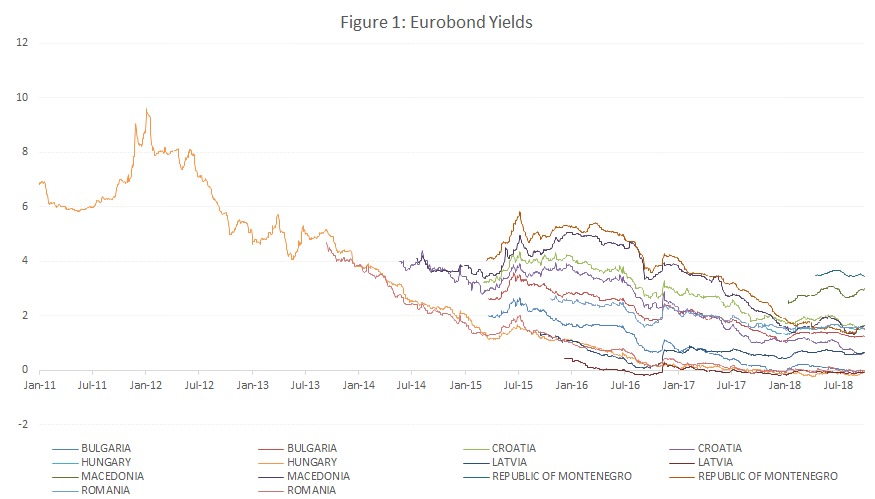

These arguments are both factually wrong and economically shallow. Let’s start with the eurobond rates. Figure 1 shows the data on eurobond rates for a group of Eastern European countries – because it would be better to compare Albania to its peers rather than African or Latin American countries. Two things should become immediately clear.

First, the yield on Albania’s current eurobonds, purchased at a 3.5% rate, is not below the region’s average. In fact, it is higher compared to everyone else. Even a corrupt pseudo-democracy like Montenegro is currently enjoying lower rates at 3.4%.

Second, borrowing costs have been decreasing across the region. Albania is just part of that regular trend. What is even more disappointing from an economic perspective, is the reason behind this trend. This is not due to some sort of “miracle,” but the exact opposite. The lower borrowing costs for the governments, helped by a strong monetary stimulus from the European Central Bank after 2012 eurozone crisis, reflect an unwillingness to provide credit to the private sector. Governments are enjoying lower costs because they are the only safe alternative for investors, and that is not a preferred policy outcome.

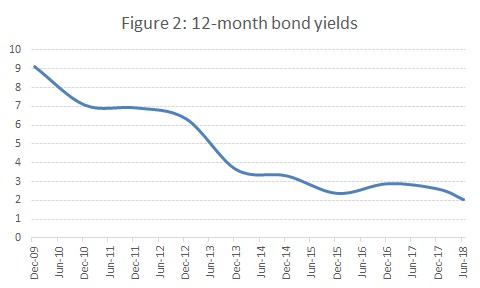

The same can be said for internal borrowing costs, as well. Mr. Hausmann claims that there is some sort of miracle underway here, as if the government were previously facing “sky high” rates. This again turns out to be untrue. As can be seen in Figure 2, which shows the average yield on the 12-month bond of Albanian government, costs were going down well before 2013, when the first Rama government came to power. Unfortunately, the economic causes behind this are what should really worry an economist. The decrease in bond yields is due to the Bank of Albania lowering their base interest rate ever since the 2008 shock and the ensuing worsening economic conditions.

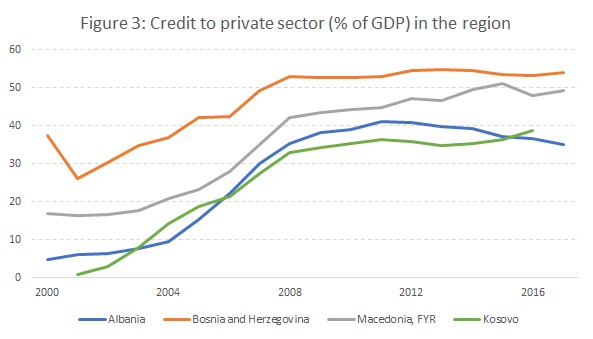

In fact, the lack of financing for the private sector has become so problematic that after years of growth in the financial sector, measured as private credit over GDP, the ratio has actually decreased in recent years, as seen in Figure 3. Even in a problematic region like the Balkans, where international banks are pulling out, Albania still stands out as arguably the worst performer. This again disproves Hausmann’s “miracle” claims. Not only has he fabricated an entire story regarding the government’s financing abilities, but he appears oblivious to the economic fundamentals driving these outcomes. The decrease in borrowing rates, a regional trend, is not due to some economic miracle, but the expected result from a period of sluggish growth.

The next major claim is that Albania is somehow unique in its uptick in growth prospects. As Hausmann explains:

Five years ago, Albania faced a truly ominous situation. With Greece and Italy reeling from the euro crisis, remittances and capital inflows were falling and the economy suffered a severe slowdown.

Fast-forward to the present: the economy is growing at a robust 4.2% rate. What was the secret of Albania’s turnaround? First, as opposed to many countries that delay action until it is too late, Prime Minister Edi Rama called in the IMF as soon as he got into power in September 2013.

But is this really true? Did Albania truly face an ominous situation, which was somehow miraculously saved only by the IMF intervention of 2013 which only Prime Minister Rama had the guts and foresight to call in? Again, the data tell us a very different story.

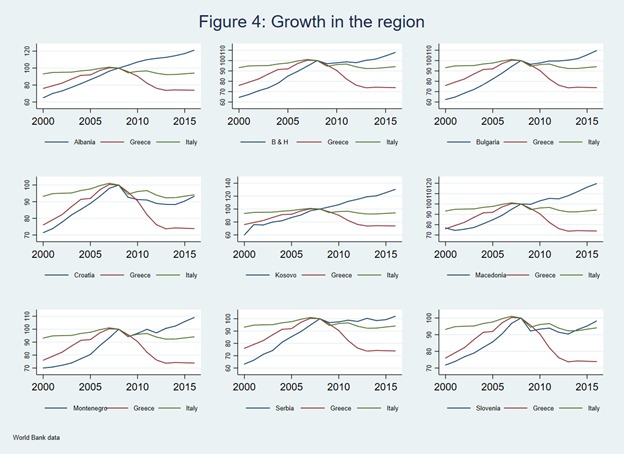

If we look at a GDP index for countries in the region, setting 2008 = 100 (this is a common method to compare between growth trends of countries with different levels of GDP) (Figure 4), we notice how the financial crisis hit Italy and Greece, the region’s main trading partners, the hardest. As a consequence, it played a part in slowing down almost every other economy in the region. The second eurozone shock of 2012, partly due to a slow reaction by the ECB which was roundly criticized at the time, was felt particularly hard as it killed off a nascent recovery across most of the continent.

Yet compared to most other countries in the region, Albania’s slowdown was much less severe. It never went into negative growth territory and the trend of growth did not deviate as much from previous years compared to other countries. Most importantly though, the recent uptick in growth prospects is something that can be seen across the region, and coincides mostly with Greece and Italy slowly emerging from the crisis. There is no major “Rama” effect here, nor is this due to some miraculous and unique IMF intervention that only Albania called in at an appropriate time. It is an improving regional and world economic outlook that has carried along with it the other smaller economies in the regions, even more rapidly in some instances.

Of course, in order to be intellectually honest, there is an important underlying caveat throughout this story that is worth mentioning. The countries which performed best during the eurozone crisis by experiencing a very mild slowdown (Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Macedonia), are also the poorest in absolute terms. Their ability to grow during this period is a result of the fact that they have room to grow since they are only starting to approach GDP per capita levels comparable to the rest of the region and the continent. Again, this introductory economics growth theory outcome (known as “economic convergence”) should be quite familiar to someone working in the field like Hausmann, but yet again he seems to forget the very basics of his profession when propaganda duty calls.

The last big claim that Hausmann makes is regarding the source of this recent growth in Albania. Reading his article one can feel awestruck at the name of policies and sources claimed.

Fast-forward to the present: the economy is growing at a robust 4.2% rate, led by double-digit export growth in agriculture, mining, manufacturing, energy, tourism, and business services.

In agriculture, the development of aggregators helped small farmers connect to better technologies and more lucrative markets, creating a boom in vegetable exports. Likewise, consultative groups in manufacturing and tourism identified areas for improvement.

This, of course, is partly due to some incredibly policy-making by Hausmann himself and his colleagues (the generous Open Society funding have to be justified somehow):

Mentored by Matt Andrews of Harvard Kennedy School of Government, policymakers used an implementation strategy based on a problem-driven iterative process, which starts by nominating a problem, identifying its causes, and devising ways to fix it.

Moreover, the country’s ambassadors are now being used in a concerted strategy to promote foreign investment through direct engagement with firms. And policymakers are now engaging Albania’s diaspora.

Ah yes, that incredible approach of identifying problems and trying to fix it! How very innovative. Once you also throw in economic diplomacy, how can one resist?

But really, what does the data say about these claims? Well, for starters, in what seems to be a common theme throughout his article, Hausmann doesn’t even appear to know the actual major sources of growth during the last 4–5 years in which he supposedly provided policy advice to the Albanian government. INSTAT’s (the Albanian statistical agency) very own data tell us that the major source of growth initially were two major infrastructure investments planned well before the new government (TAP and HEC Devoll Hydropower).

Recent years have seen an uptick in real estate investment. Unfortunately, this is also problematic for two reasons. First, the Albanian banking sector was also over-leveraged in the sector before the 2008 and 2012 crisis. Policy reports written during the period underlined the need to diversify the sources of growth in the economy and move away from construction as a major player. In fact, diversifying the sources of growth was the major part of Hausmann’s speech to ministers and ambassadors a year ago. Yet it seems like Albania is repeating the same cycle.

Second, unlike the first real estate boom cycle in 2004–8, this latter one is no longer being financed by the financial sector. As we saw before, lending to the private sector has decreased, with construction being one of the main culprits. European-owned banks especially are under strict guidance to stay away from the sector. This has raised suspicions about the source of money which is founding the construction boom. If this is truly drug money being laundered, as is a growing suspicion, well, Hausmann needs only to look at his native Latin America to understand the economic and political implications of this process. It does not bode well neither for the economy nor for the democracy of Albania.

And what about that newly empowered economic diplomacy? Yet again, there is much smoke without a fire. Albania has failed to attract any major foreign direct investment projects recently and has failed to keep up its previous trend. The two major projects, TAP and Devoll HEC, remain the last important foreign investments that the country has been able to attract.

Finally, Hausmann made other, minor claims regarding fiscal stability that are equally unfounded, but we’ll leave those for another time. For now, let’s finish by repeating a statement from one Nobel Prize winner to describe the latest Nobel winner, who made his contributions in the very field of growth and development:

You will almost never see an economist whom the academics themselves regard as important or interesting. For example, neither Robert Lucas, without question the most influential economic theorist of the 1970s, nor Paul Romer, arguably the most influential theorist of the 1980s, has ever appeared on any public affairs program. – Paul Krugman (1994)

There is a reason why. Most honest academic economists, such as Romer, would probably tell unsuccessful governments that it is them who are blocking the path of development for their respective countries, and not the lack of some “miraculous” ideas.