Perceived European Invincibility In Colonial Wars Led To Arrogance And Death On Massive Scale

Summing up colonial warfare of the 19th century British poet Hilaire Belloc wrote in 1899 “Whatever happens, we have got the Maxim gun, and they have not.” However, Belloc’s comment often repeated by historians and in textbooks misses the fact that this period’s conflicts were often determined by more than just modern firepower.

Sure such victories could be impressive in 1879, an immature Zulu regiment or impi of perhaps 4,000 was held off for two days by 139 British soldiers at the Battle of Rorke’s Drift in modern South Africa. In 1897, a group of 21 Sikh soldiers fighting for the British held a small fort at Saragarhi on the Northwest Frontier (in today’s Pakistan) against a much larger force. The Saragarhi fighting to the last man their suicidal resolve against over 6,000 hostile Afghan tribesmen allowed them to hold out for hours and delay the hostile force long enough for British reinforcements to rush to the remote region. The Northwest Frontier campaigns waged by the British against Afghan tribes saw numerous situations where small garrisons held off against larger Afghan forces due to superior firepower. In 1885, a French force of 4,500 fought a Chinese force of 35,000 in Taiwan to a draw.

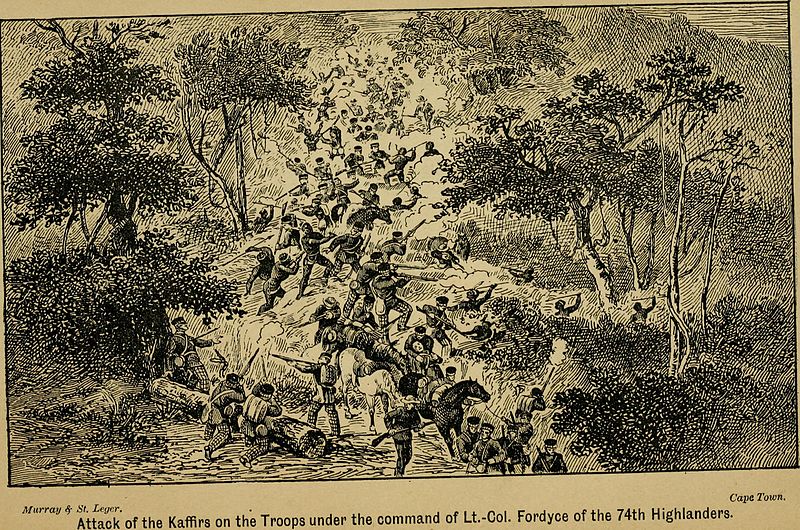

However, these victories often masked the fact that well into the 19th century, indigenous forces were able to pull off unlikely and surprising tactical victories, in particular with careful use of terrain, mobility, and firepower.

In 1864, a British force of 1,700 soldiers equipped with artillery and superior rifles attacked a Maori force of 235 dug in behind a stone fortress at Gate Pā, in New Zealand. The Maori force lead by Rawiri Puhirake repulsed the British assault on Gate Pā at close quarters with heavy losses for the British. As the British retreated its defenders subsequently slipped away under the cover of darkness.

Indeed between 1876 and 1882 modern armies were defeated in a number of important engagements against indigenous forces. America’s centennial celebrations were dampened in 1876 by the news of the defeat of Colonel Custer Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 by a highly mobile force of Native Americans. During the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 the British were defeated at Isandlwana and again at Hlobane fighting a Zulu army primarily armed with thrusting spears. Several other battles were close run affairs and in one not inconsequential skirmish Napoleon IV was killed by a Zulu patrol. In 1880, the British suffered another defeated at the battle of Maiwand in Afghanistan with roughly a thousand casualties. In 1882, the forces of Samori Toure in defeated a French force equipped with modern artillery at the Battle of Woyowayanko in West Africa. Samori Ture victory was not forgotten he was the great-grandfather of Guinea’s first president, Ahmed Sékou Touré.

None of these battles were decisive; but, Ethiopia’s victory at the Battle of Adowa in 1896 during the first Italo-Ethiopian War effectively secured that kingdom’s independence. Key to the Ethiopian victory was possession of repeating rifles – which had also been a key to the victory of the Sioux at Little Big Horn. The smaller Italian force lacked modern fire arms and artillery. In short Ethiopia and Afghanistan were able to maintain their relative independence during this period in part because of their military prowess.

These victories came when indigenous forces often employed or understood modern technologies to their advantage. The Zulu commanders were well aware of British firepower and largely sought battle where the terrain nullified this advantage ( though they feared British bayonets even more). This was often lost on imperial analysts who saw such defeats as one-off losses. Indeed histories of the period have little to say about technology and instead often focus on the less successful traditional remedies. In North America, the Ghost Dance created by Native American religious leaders in the late 19th century convinced some of its followers that the new rituals would protect them from bullets. Some of those involved in the Boxer Rebellion in China and the participants in the Maji-Maji (1905-1908) in what is today Tanzania held similar beliefs. In 1906, during a Dutch assault on a palace in Bali, the Balinese stabbed themselves and mocked the Dutch military superiority by throwing coins at them.

Defeats were over-looked and the victories over stated. A large number of Victoria Crosses were awarded to British soldiers who fought at Rorke’s Drift in part to distract attention from the defeat at Isandlwana. These often one sided victories added to the myth of European military invincibility. It is not a coincidence that sports coverage in newspapers emerged at the same time as the war correspondent. Such was the myth of European invincibility that even Japan’s defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) did not lead to re-thinking.

Indeed the lure of easy victory and jingoism amongst European populations contributed to the headlong rush towards the Great War in which Europeans learned that machine guns could be just as effectively deployed against European armies. This led to the carnage of the Somme and Verdun with World War I becoming the first inter-state conflict in which more individuals died due to wounds (from machine guns) then illness. A possibility not envisioned by writers like Belloc, but a conflict which in many ways set the stage for much of the world’s geopolitical troubles today. A lesson that those involved in planning future conflict would be well to learn.